Between Water, Chalk and Time: Archie Moore at GOMA

Archie Moore’s kith and kin on show at GOMA until 18 October 2026.

Although its celebrated moment was in Venice back in 2024, I only physically encountered Archie Moore’s kith and kin on a recent trip to Brisbane, where it remains on show at GOMA until 18 October 2026. After seeing the work, I found myself in two minds about writing anything at all, wondering if it might simply feel like old news. It has been covered from every angle, examined by critics, curators and journalists since its debut in Venice. Yet this was my first encounter with the work in person, and that felt reason enough to put something down. There is a difference between reading about kith and kin and standing inside it, letting the room settle around you and discovering what the work does when it meets your own pace, your own attention.

The installation carries the weight of its own reputation. Moore’s presentation for the Australian Pavilion won the Golden Lion for Best National Participation at the Venice Biennale, a milestone no Australian project had ever achieved. Before you even enter the room, GOMA makes that triumph clear. The award sits in a glass case at the entrance, cradled inside a red silk box. The gleam of the winged golden lion feels almost ceremonial, a quiet reminder of the global attention this work has earned.

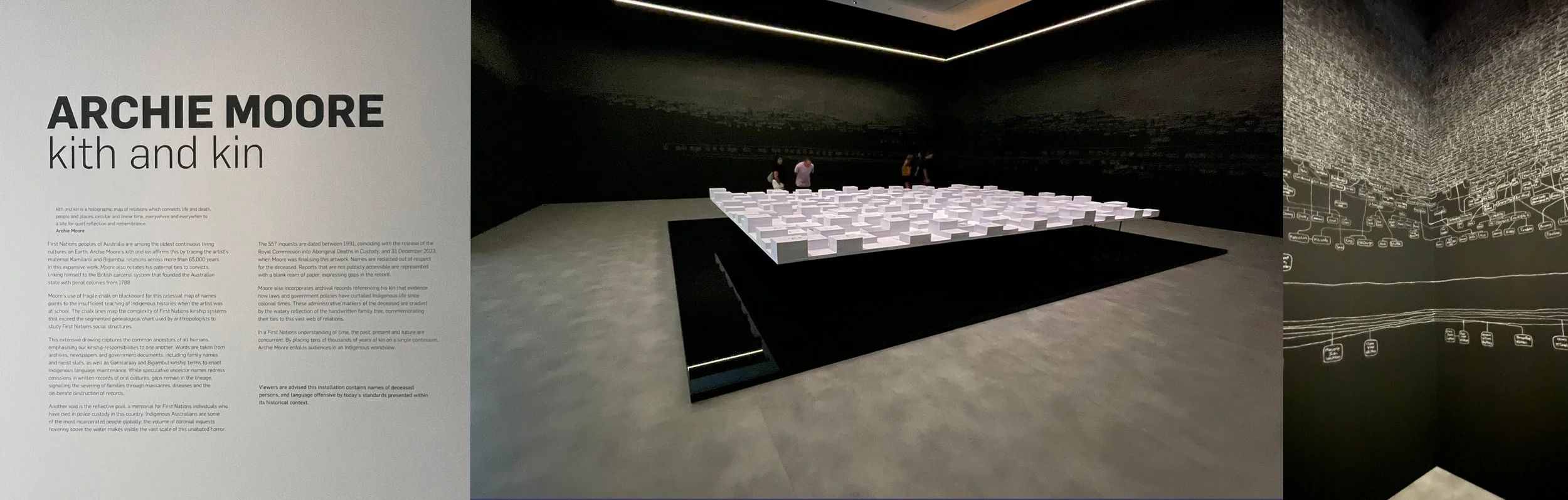

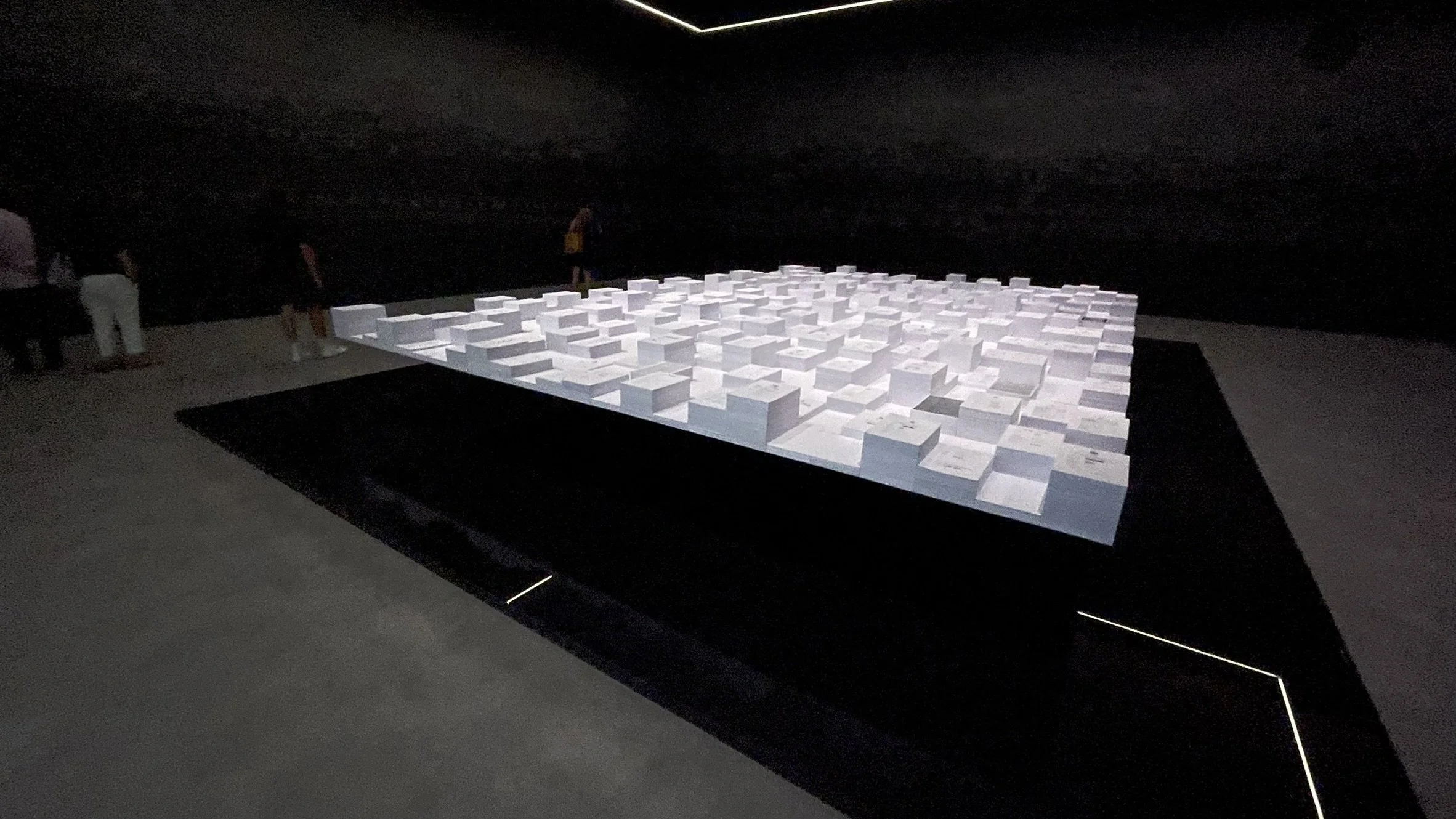

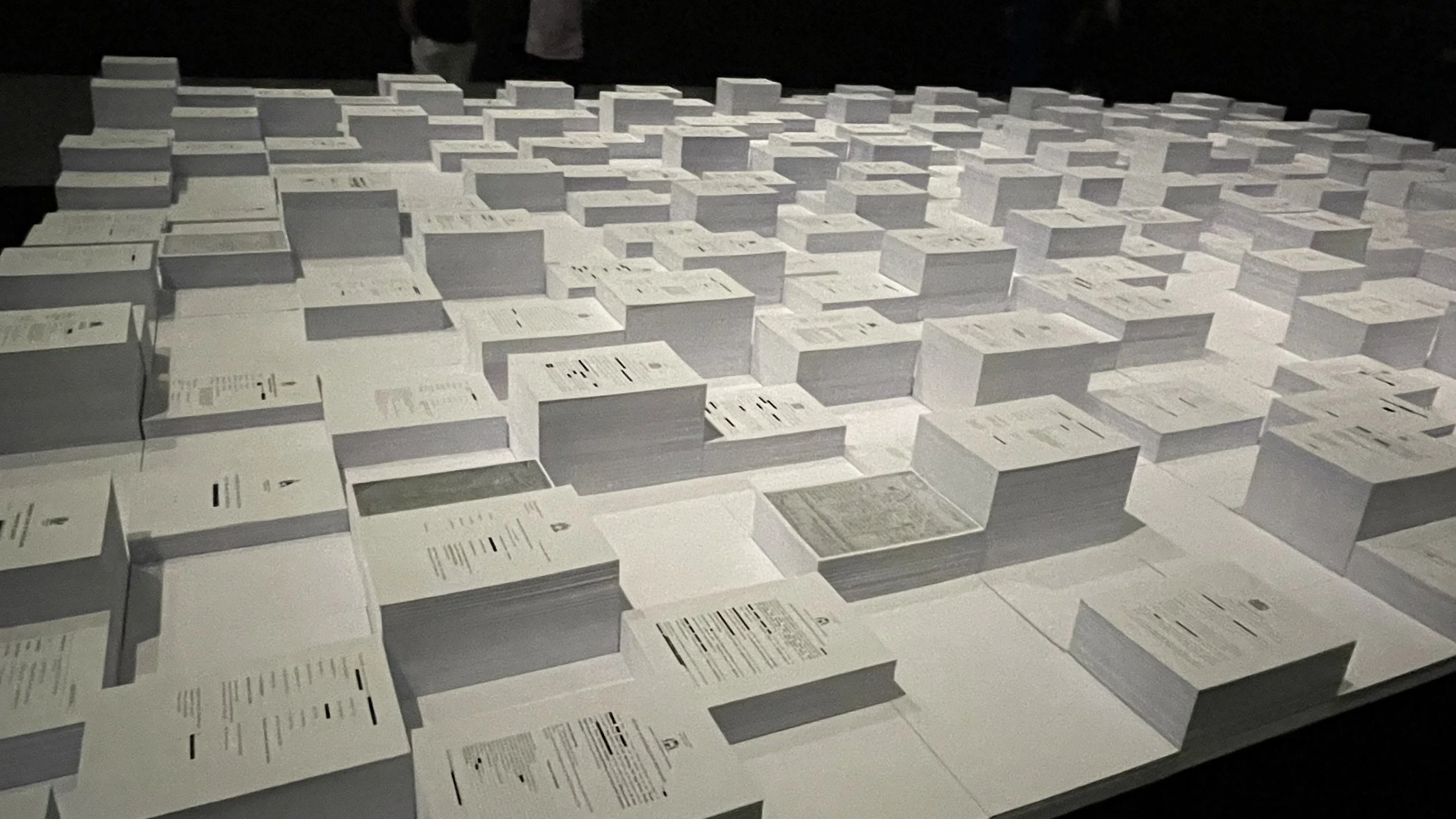

After the dazzling brightness of the award, a gallery attendant suggested I move slowly. The room, they said, was dim and my eyes would need time to adjust. They were right. The space is almost entirely black and white, softened by the low light. A rectangular pool of water anchors the centre of the room, its surface so dark it acts like a mirror. Floating above it is a long table covered in stacks of A4 documents. They rise in uneven columns, something between redacted state archives and the miniature skyline of a city. The longer you look, the more the water below turns the whole scene into a reflection of itself, as if memory is doubling back.

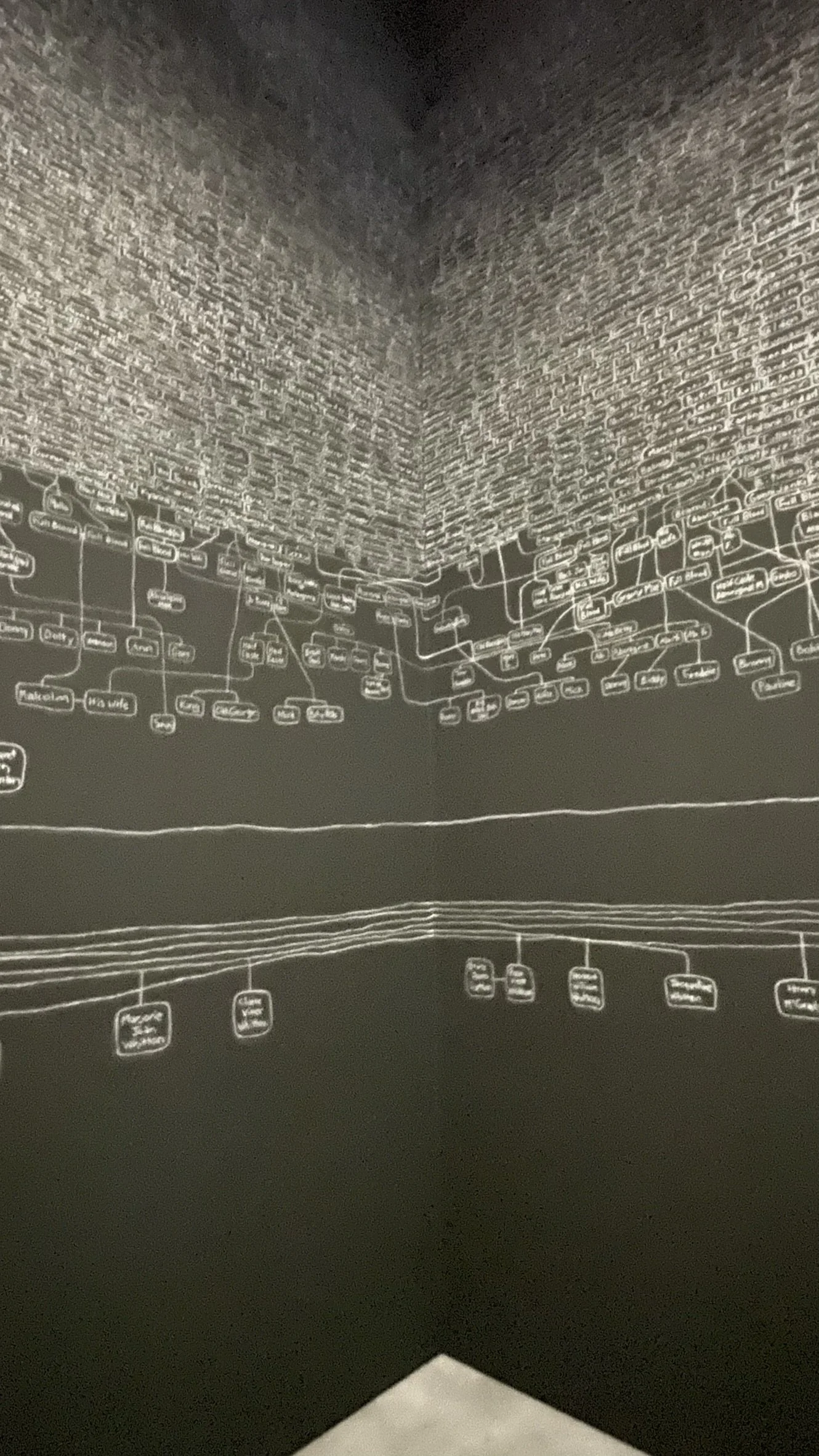

The installation unfolds quietly. Once your eyes adjust, the walls reveal the work’s true scale. Every surface is covered in Moore’s vast family tree, drawn in white chalk across the black ground. The diagram wraps around all four sides of the room, beginning at the viewer’s waist height and rising toward the ceiling, where the names scatter like a field of stars and press closer together the higher they climb. Anyone who has tried to map a family line knows how messy these diagrams can become. Here, the precision is astonishing. The chalk marks are steady and deliberate, one name leading to the next, forming a single uninterrupted lineage.

Stepping closer is necessary. The darkness of the room forces you to lean in and read each name, and that slow, intimate movement feels intentional. The family tree becomes something you navigate with your body rather than simply observe. It is a visualisation of deep time, an affirmation of First Nations continuity stretching back more than 65,000 years, but it is also a record of fractures, marking violence, disease, dispossession and the silences forced by colonisation.

The documents at the centre of the room form the other half of this story. Most are coronial reports relating to deaths of First Nations people in police custody. They stand as a memorial for individuals whose lives were reduced to administrative language. The reflective pool beneath them draws everything together. The family tree on the walls is mirrored in the water, and the documents sit above their own shadow. It creates the feeling of standing between two worlds, the ancestral and the contemporary, the remembered and the redacted.

Moore’s installation is both personal and political. His own family records are folded into the stacks on the table, reminding viewers that these histories are lived realities rather than distant facts. The work confronts the breakages that colonisation forced into his family line, while still asserting the immense resilience that continues through culture, language and kinship.

Encountering all of this in person at GOMA deepens the impact. The room requires patience and attention. It slows your thinking. The chalk on the walls feels fragile, as if it could be wiped away, and that fragility turns the act of looking into a form of care. Every name becomes a presence rather than a notation. The space carries a steady, quiet gravity.

What stays with you long after leaving the room is not only the history mapped across the walls but the sense of responsibility it implies. Moore’s vision extends beyond biography. The installation gently insists that kinship runs further than family lines, that we are connected to each other across time, place and culture. In its scale and intimacy, kith and kin becomes a reminder that memory is a shared terrain that needs tending.

The Biennale may be over, but the power of Moore’s installation has not dimmed. The calibre of the work, and the prestige it has earned on the world stage, make its extended showing at GOMA feel entirely warranted. It is rare for a piece of contemporary art to gather this level of attention, and even rarer for audiences in Australia to have the chance to stand in front of it without the noise and rush of an international festival.

This presentation gives the work the prominence it deserves. kith and kin is a deep and provocative installation shaped by long research, personal courage and a quiet kind of authority. Encountered here, away from the glare of Venice, the room settles around you and the experience becomes slower, fuller and more personal. It is a work that continues to earn every accolade attached to it, a work that stays with you long after you step back into the light.